Children raised in single parent homes without dads are five times more likely to be poor. In fact, according to most recent census figures, almost 39% of children in families raised by single mothers live in poverty. Census figures also bear out that children raised in fatherless homes comprise 63% of youth suicides, and 90% of all homeless and runaway children. Other studies indicate 85% of all children exhibiting behavioral disorders come from fatherless homes (Center for Disease Control); 71% of high school dropouts come from fatherless homes (National Principals Association Report on the State of High Schools); and 75% of adolescent patients treated for substance abuse come from fatherless homes (Rainbows for all God`s Children). If you look at statistics from the US Department of Justice, 70% of juveniles in state-operated institutions come from fatherless homes and 85% of youths sitting in prisons grew up in fatherless homes.

Those are the numbers but where are their stories? More significantly, where are the stories of adolescent boys who may feel social, cultural and gender pressures to grow up before they’re ready? Where can readers go to learn what it’s like to be a guy growing up with a mom struggling to pay the bills and put food on the table in a culture that encourages these boys to man up for the family?

Readers can begin with two young adult authors who consistently write about these issues: Prolific and award-winning writer Chris Lynch and relative newcomer Mathew De La Pena.

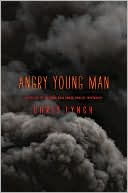

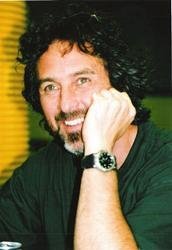

Chris Lynch’s new young adult novle Angry Young Man, with starred reviews from School Library Journal and Publishers Weekly, shows the darkest sides of the way our culture tries to make men out of boys through the story of two brothers, both attending a community college while fretting over their mother’s financial difficulties. Older brother Robert who narrates this story wants readers to understand his younger brother Xan, a very angry young man who grew up in Robert’s shadow. After Xan falls in with a group of activists and a loan shark hounds the family, Robert fears the violence he believes Xan could commit. While this novel reveals the complex relationship between the two brothers, it also explores what Booklist reviewer Ian Chipman so aptly describes as “the claustrophobia of uncertainty about the forces that threaten the family even as he dwells on how he could have done better by his brother.”

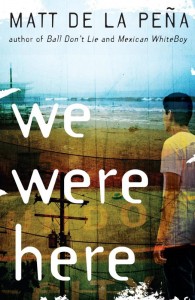

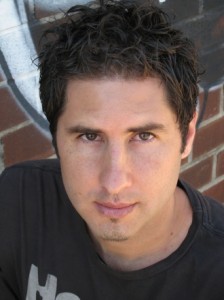

Mathew De La Pena made his debut as a young adult novelist with Ball Don’t Lie. This was followed up with Mexican White Boy, We Were Here and De La Pena’s most recent novel, I Will Save You. All three novels focus on family and culture, the question of identity and the affects of growing up with a missing parent.

Where Lynch’s Angry Young Man traces the spiraling effect of social, family, cultural and economic pressures on young adults who are made to take responsibility too soon, We Were Here begins with Miguel, an adolescent who has been placed in juvenile detention and required to keep a journal to atone for a tragic event that has changed his life and family forever. At the center, Miquel befriends and escapes with Rondell, a mentally challenged teen prone to violent outbursts, and Mong, a boy troubled with numerous physical and emotional problems. As the boys make their way toward, Mexico, Miguel reveals his grief through the details of his family’s tragedy.

Both Lynch and De La Pena responded to the question of how boys, especially boys in fatherless homes, are often expected to take on adult responsibilities too quickly.

Q: Are teen boys taught to stuff their emotions?

Chris: I am not sure if teen boys are exactly taught to stuff their emotions. I think it is more like, in a lot of indirect ways they are signaled to do so. More and more I find myself looking at the whole history of humankind and I feel that the source of almost everything awful tends to be traceable to two words, Macho Bullshit. Anger is the only acceptable face of vulnerability in so many situations. Guys intuit that they have to bluff and bluster, threaten posture in order to mask any softness. Perceived weakness is seen to be even worse than the real kind, and this looks like the prevailing mode in popular culture as well as international relations.

Matt: I don’t think teen boys are overtly taught to bury their emotions. That being said, if you grow up like I did, in a super machismo family, with a tough old man and tough uncles, you’re going to try and be like them. But I don’t think the emotions are deleted completely. They’re just less public and more personal. Emotions come out in actions and re-actions. I love following a character who is dealing with something that threatens his or her cool (by the way, many of the girls I write about are a bit hardened, too. Maybe sometimes it’s a neighborhood thing, or a socio-economic thing.) But when people tell me my books are about tough kids who bury their emotions, I’m surprised. Miguel, my main character in We Were Here, is extremely emotional through the book. He may not cry or talk things out, but he’s feeling things throughout. Sometimes boys keep their emotions in secret hiding place, but it doesn’t mean they’re not feeling things.

Q: Do you think teen boys are raised to be the ones who take care of their families if a father figure isn’t in the picture? How helpless does this make a minor teen feel?

Chris: My own gut says that young males do not seem to be prepared to take over. It depends on the reason for the father’s absence, of course, but I think the ongoing tragedy of fathers who leave willfully and do not play a part in their kids’ lives (as opposed to, say, dying) is that they set up the notion that being a father is somehow optional in a way that being a mother is mostly not.

Matt: I definitely think teen boys, at least the ones in my novels, are shoved into the caretaker role if dad isn’t around. In fact, I’ve seen this so many times with friends. Boys as young as thirteen filling the role of “man-in-the-house.” This really robs a kid of his kid years. It happened to my dad. And because that was what he knew (maybe) he had a family of his own by age 18.

Q: If a teen is taught to stuff his emotions and then made to feel responsible, what happens when he feels he’s in over his head?

Chris: An emotionally stunted teen who then becomes a sort of household authority figure would appear to be in deep trouble when circumstances became overwhelming. One has to learn to properly emote, or else it comes out in its own frightening ways. That pressure does not just dissipate, it bursts out somewhere along the line. And then you have the added sadness of passing that style onto the poor kids who are subjected to it.

Matt: He’s like a trapped animal. He lashes out. I used to work in a group home, and sure, many of the crimes these kids had committed were immature, but some were crimes of desperation. Standing up for family members or enforcing honor codes. And the most interesting crimes were the ones where a boy simply felt like was trapped in some way. I know some of the kids felt more comfortable at the group home than they did at their real homes (though this was rare). He may not have the skills to identify these feelings, or communicate them, but you can see it when they talk about “back home.”

I know some boys would rather punch or be punched than really dig deep about how they’re feeling. That’s why I like to let readers watch my characters rather than supply a bunch of internal exposition. It feels more honest for my books.

2 comments for “Sad, Scared, Angry: Young Men in YA literature”