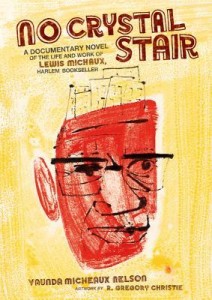

To kick off Black History Month, I interviewed Vaunda Nelson, author of the Coretta Scott King honor book No Crystal Stair: A Documentary Novel of the Life and Work of Lewis Michaux, Harlem.

- No Crystal Stair by Vaunda Nelson

1. Why do you think it’s important for us to honor the contributions that men and women like Lewis Michaux made to society and, in particular, to black culture?

For the same reason we honor contributions made to society by any man or woman. Histories of individuals like Lewis offer inspiration, instruction, as well as the enjoyment that comes with darn good stories. By recording and celebrating their stories, we provide ourselves with a reservoir of experience from which to draw as we navigate our lives. With regard to black culture in particular, I do feel an extra sense of pride when I can point to the accomplishments of the likes of Lewis Michaux and Bass Reeves. The unveiling of these unsung contributors adds new dignity to our heritage, not just for blacks but all Americans. Their stories raise the standard for those (young people in particular) who most need role models.

2. You’ve honored him by writing this book. How can others honor him (and men and women like him)?

We can honor Lewis by reading, reading to understand and nurture ourselves, and by trusting and living Lewis’s belief in the power of knowledge. By passing on this legacy to our children, our grandchildren, and anyone in our sphere of influence, we can (as Reverend Charles Becknell said of Lewis) “leave something that spreads to other people.”

3. Can you talk about the contrast between Lightfoot and Lewis’s approaches to saving men’s souls (because I would argue Lewis was in the business of saving men’s souls just as much as his preacher brother) as well as the lasting legacies of both men?

I couldn’t agree more that both were in the business of saving souls. It’s more complex than this, but, stated simply, Lightfoot put his faith in God while Lewis put his faith in knowledge. Lightfoot was devoted to the spiritual, eternal life, providing a way to Heaven. Lewis was focused on the survival and elevation of the black man here on earth. He said, “You can’t protect yourself if you don’t know something.”

I’m sure each of the brothers subscribed to some of the other’s philosophies and prescriptions for life. Lightfoot respected Lewis’s push for intellectual advancement. And even though Lewis left the church, he didn’t abandon God. I believe this because when I visited his store in 1968 at the age of 14, he gave me a copy of the King James Bible. Still, Lewis was fiercely independent and never completely embraced any organized religion. He said, “Never lose your individuality.”

4. One of the aspects of the book that I personally found most engaging was Lewis Michaux’s engagement with ideas and leaders coming from across the water—from men like Marcus Garvey (Jamaica) or Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana). This is of course part of the Pan-African movement that many black leaders engaged in for much of the 20th century. Can you talk about Michaux’s role in that movement? Can you talk about why pan-Africanism seems like a less salient force in the American black community today? (Though some would argue that hip-hop has perhaps replaced the political sphere as a force of consciousness raising and a plea for brotherhood among people of African descent worldwide—and I found Lewis’s ideas about music, though sparse, to be interesting….)

I’m no expert on the Pan-African movement. I’m just a storyteller who enjoys history. My understanding is that Lewis (like his father) found inspiration in Garvey’s commitment to blacks building their own businesses, creating their own communities, becoming self-sufficient. This is why Lewis connected with Lightfoot’s Virginia farm community project, even though it was plagued by complications. Marcus Garvey was a doer with a plan for the unification of black people globally. Lewis applauded his conviction in the face of great financial and political odds. Lewis learned from Garvey but walked his own path. Garvey’s way was a physical return to Africa. Lewis’s was an intellectual one. Black books were the resources he provided for those who visited his bookstore. Lewis saw the value of blacks returning to their ancestral homeland, not necessarily to stay, but to learn. He believed that individuals must understand the past in order to move forward. Lewis enabled American blacks to experience Africa through literature.

In Garvey’s Pan-African era, many blacks had parents or grandparents with strong memories or stories passed down of their native lands. Today, American blacks are much farther removed from these kinds of personal connections and so may not be able to identify with Africa in the same way.

5. This is a book that is almost exclusively about a grown man, yet it’s a young adult/children’s book. Can you explain why you wrote this as a y.a. book?

I write for children, so it was natural for me to want to share Lewis’s story with young people, but I hope it speaks to adults as well. Youth is a time that is heavy with searching, tripping, falling, getting back up, slipping, finding ground, flailing, and finally flying. Lewis’s journey embodied this, so I suspected it would appeal to teens. And as a bibliophile, I was thrilled to share the story of a man who used books as a compass in his search for self. For many people it seems that education is primarily a means to an end — employment. Not necessarily a bad thing, but Lewis was promoting something greater — being an educated person in the world. I hope readers come away with a deeper desire to know more, to crave the richness that knowledge can bring to everyday life.

6. Can you make suggestions of other books teachers could pair this with to teach black history and the civil rights movement?

This is difficult because there are so many possibilities. I am partial to poetry, so here are a few ideas that come to mind: The Dream Keeper and other poems by Langston Hughes, Here in Harlem: poems in many voices by Walter Dean Myers, Talkin’ About Bessie or Jazmin’s Notebook by Nikki Grimes, Children of Promise: African-American Literature and Art for Young People edited by Charles Sullivan, Carver: A Life in Poems by Marilyn Nelson, or almost any poetry by Nikki Giovanni.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley would be an interesting companion book. Also, the writings and speeches of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. provide excellent perspectives on the issues of the time.

Vaunda, thanks for sharing your thoughts with The Pirate Tree.

2 comments for “No Crystal Stair: an interview with Vaunda Nelson”