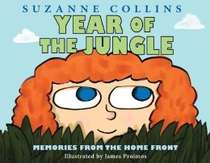

“My dad has to go to something called a war. It’s in a place called Viet Nam,” explains Suzy, the younger-self narrator of Suzanne Collins’ autobiographical picture book The Year of the Jungle, Illustrated by James Proimos (Scholastic Press, 2013).

“My dad has to go to something called a war. It’s in a place called Viet Nam,” explains Suzy, the younger-self narrator of Suzanne Collins’ autobiographical picture book The Year of the Jungle, Illustrated by James Proimos (Scholastic Press, 2013).

The story begins poignantly before Suzy’s father leaves for war, with Suzy on her father’s lap as he reads her The Tale of Custard The Dragon by Ogden Nash, and with the foreshadowing observation, “Even though [Custard] always feels afraid, he is really the bravest of all. And that’s what makes him special.” But on page five Suzy’s usually happy face is worried, her father is going to war, he will be gone a year. In a spot-on child’s point of view, she wonders where Viet Nam is and how long is a year. She says, “I don’t know what anybody’s talking about.”

Collins skillfully explores the effects of war on those who serve and their families, all the while showing those effects through the strict point of view of young narrator Suzy. When she first learns that her father is in a jungle, she imagines it to be like her favorite cartoon, and wishes she and her cat could go on an adventure in a jungle, too, without any understanding of what it means to be at war. She measures time in holidays, wondering with each how much longer until her father comes home. She eagerly awaits his postcards, which start out light and teasing, before becoming serious and worrisome. As some of the dangers and realities of war begin to filter in, the fanciful jungle images turn to worry and then to fear, culminating in Suzy’s startling glimpse of guns and explosions and soldiers on television. Time passes without postcards from her father and Suzy fears her father is “lost in the jungle.” She worries that “maybe he can’t get out. Maybe he never will.” When he suddenly arrives home, Suzy is, of course, happy. But she observes he’s not the same, that sometimes “he is here but not here.” Sometimes he “is back in the jungle.” She feels the need to communicate that she understands, and does so in an age-appropriate way. And yet the story ends where it begins, with Ogden Nash and his dragon, with Suzy and her father. Suzy observes “Some things have changed but some things will always be the same.”

What is remarkable about Collins’ telling is that the reader remains in Suzy’s limited point of view, experiencing her innocence, her confusion, her growing understanding, her observations of the adults around her, her fears, her worries, and ultimately her observations of her post-war father. And while the conflict is the war in Viet Nam, the experiences could be those of a child today with a parent or sibling or other trusted adult serving overseas. The growing unease and eventual efforts to understand could mirror that of a child struggling with a parent’s illness or incarceration or other separation from the child. The struggle to interpret and understand an adult world is a universal experience of children. Whatever the catalyst, the thing to understand, the experience remains.

Adult readers will appreciate the subtle insights in Suzy’s observations and questions, and the greater depth in the details Suzy conveys without understanding, like her sibling’s actions and reactions to their father being at war, and Suzy’s own instincts to hide her fear from her mother. Younger readers (and listeners) will relate to the fears of a child, beginning to understand there is a reason to worry, struggling to interpret that which adults aren’t readily explaining. Those who have experienced a parent’s deployment will especially relate to the fears and worries, and to the changes war can cause in a loved one. But even those children who have not experienced separation or a loved one’s deployment will be able to relate to Suzy’s confusion, her efforts to understand. A child who has suffered loss or separation may be comforted in knowing she is not alone, that other children experience difficult things, too.

Although Proimos illustrations at first felt too cartoonish for such a serious book, they are in perfect harmony with the child-centric point of view and wide-eyed innocence of the young narrator. On the second reading I began to appreciate that the illustrations enhance the sense that the reader is experiencing the world through Suzy’s eyes, as she sees it and herself, as if the images on the page reflect a child’s emotional drawings. His use of wordless, double-page spreads to show Suzy’s imaginary adventures in the jungle, and then her growing worries and understanding, add depth to the written text and help to show the way in which a child might process these experiences.

Some may balk at introducing a book that realistically portrays war, even through the age-appropriate lens of a child’s point of view, to young readers. However, the reason to share this book with children is implicit in the story itself — they absorb and understand far more than we know, maybe than we want. Children today live in a world saturated with conflict. Perhaps Suzy’s story, and her observation that “Some things have changed but some things will always be the same” can be a comfort, or the entry into greater discussion.

2 comments for “Review: Year of the Jungle by Suzanne Collins, Illustrated by James Proimos”