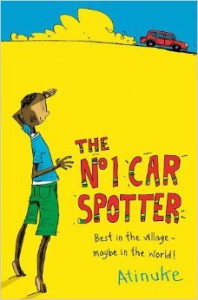

I suppose it’s sort of an odd choice to review The No. 1 Car Spotter by Nigerian author Atinuke in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. But it’s not as odd as you might think. Bear with me and see below.

Oluwalase Babatunde Benson is the hero of this book. His nickname is No. 1. As in THE No. 1. As in, The No. 1 Car Spotter in his whole village. He gained this nickname because there’s no other hobby available in his village. But a No. 1 road runs straight through his village and No. 1 can tell what kind of car it is simply by hearing the engine. Together with his family, No. 1 figures out how to solve the problems they face–from how to get all their goods to market day when the cart has broken to how to buy medicine for Grandmother when they have no money.

Let me start by saying that this humorous chapter book set in a Nigerian village far from the city is a great way to introduce kids from around the world to life in an African village that lacks electricity, television, and tap water. But this is not a book that will provoke pity. This is a book that reveals ingenuity, a cooperative spirit, and a loving family that figures out how to solve the problems they face together in such a way that you’ll walk away realizing that they have everything they need–love and patience and family and a natural “it takes a village” mentality that we should all envy–you know, those things that material possessions, electricity, and tap water can never buy.

So why am I choosing to honor MLK Day by reviewing this book, instead of one of the many wonderful books about MLK or about the civil rights movement? OK, this isn’t a book about civil rights at all. And it doesn’t deal with “race” as a subject in the sense that No. 1 encounters racism. But it is a book about an African kid in a nothing village in the middle of nowhere and his life is influenced in both small and large ways by economic global forces that have led to unequal “development” across the globe. And in this way, though the book doesn’t “deal with” those issues, it allows you to have natural conversations with your kids or students about issues of poverty and development in Africa–issues very near and dear to the heart of anybody who cares about civil rights. Also, it does it in such a way that you–and your kids/students–won’t “feel sorry” for them.

And second of all, it is published by a small indie press, Kane Miller. And if I’m not very much mistaken, this is important for two critical reasons. First of all, it does show a sea change from the 1960s to now, that these sorts of books are being published. It shows progress. This is not a book that would have been published 50 years ago. But it’s here now and it’s funny and beautiful and beautifully produced. Second of all, if you are concerned about giving your children or your students diverse books, you need to begin looking at indie publishers. It is only due to the decentralization of publishing that started in the 1960s and 1970s, a revolution that occurred alongside the civil rights movement, that we have a large body of diverse books to present to kids. Don’t mistake what I’m saying here. I’m all for diverse books being published by the Big New York 5. But they’re not the ones publishing most of the diverse books. If you want to encourage the kind of diversity in society that MLK Jr. dreamed about, then begin to support small press publishers like this one that are out there offering books like this.That’s my sermon today. Thanks for listening.

P.S. Kane Miller and Usborne books, two of my favorite presses, refuse to retail through Amazon. So if you’re looking for their books, you’ll have to purchase them from an indie bookseller.