Ann Bausum has written numerous non-fiction books for children and teens, documenting and breathing life into lesser known stories from our past. Her books often explore critical moments in the struggle for social justice, including the fight for racial justice and the women’s suffrage movement. Her books are consistently recognized for their literary and historical merit, and have received numerous honors and awards, including recognition from the National Council for the Social Studies, the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award Committee, and a Sibert Award Honor.

Ann Bausum has written numerous non-fiction books for children and teens, documenting and breathing life into lesser known stories from our past. Her books often explore critical moments in the struggle for social justice, including the fight for racial justice and the women’s suffrage movement. Her books are consistently recognized for their literary and historical merit, and have received numerous honors and awards, including recognition from the National Council for the Social Studies, the Jane Addams Children’s Book Award Committee, and a Sibert Award Honor.

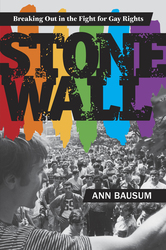

With Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights (Viking, May 2015), Bausum explores the causes and lasting effects of the Stonewall riots, and she does so with heart, a compelling narrative voice, and her characteristic attention to the details that help young readers relate to and engage with historical events. It is a watershed book for adolescent readers about perhaps the watershed moment in the fight for lgbtq+ social justice.

I am thrilled to have been able to interview Ann about this extraordinary book, and to share that interview here.

E. M. Kokie: I have heard writers wonder if they are the one to tell a particular story. Did you have any such concerns regarding Stonewall? What caused you to overcome them?

Ann Bausum: History is often written by people who share some kinship with the story, and so, at first, I hesitated to write about the history of gay rights since I, as a straight woman, could not bring an insider’s perspective to the story. Almost from the beginning, though, others—straight and gay—urged me onwards, and my interior author’s voice kept saying, “This might be your story to tell. Don’t give up on it.”

Two things happened in 2010 that confirmed all of our instincts; I write about them in some detail in the book’s author’s note. They occurred within days of one another while I was in South Dakota for the state book festival. The first was when a stranger came up to me and, out of the blue, quietly asked me, as someone who’d written for young people about social justice, to write about gay rights for teens. Then, while I was still in South Dakota, I learned of the death of Tyler Clementi, that Rutgers student who had jumped from the George Washington Bridge after an extreme episode of homophobic cyber bullying.

Tyler’s death hit me hard—I have sons close to his age, both of whom were likewise in college at that time. The thought of losing a son in such a way was heartbreaking. That was my tipping point. I had found my form of kinship—as a parent, as someone who has advocated for children through my writing. “No more Tylers,” became my motivating inner voice. I wrote this book so there would be fewer teens feeling pushed to the breaking point because their hope and resilience and self-esteem had given out.

E.M.K.: You’ve written repeatedly about movements for social change that advocated for the power of employing nonviolence in the face of violence. I’m thinking, in particular, of Freedom Riders. But with the Stonewall riots, violence becomes an essential tool for effecting change. Did that bother you?

A.B.: Actually it did! Usually I write about “good guys” who were peaceful and “bad guys” who weren’t. In this case I had to wrestle with the question: Is it justifiable for an oppressed group to use force to call attention to its oppression? Perhaps you run out of options when your very existence is declared immoral, illegal, and mentally flawed.

In the end, I had to set aside the question of the ethics of using force. The history is what the history is, and it’s my job to convey it. Readers can decide for themselves who is “good” and who is “bad,” who behaves well and who doesn’t, whether two wrongs make a right, et cetera.

E.M.K.: Stonewall appears to rely largely on contemporaneous and published accounts, rather than recent interviews. Can you discuss your decision to forgo conducting your own interviews with witnesses?

A.B.: Anytime I begin a research project, I study the available resources and make calculated decisions about how I want to use them. I probably gave more thought to the question of collecting oral histories than to any other consideration because, naturally, one hunger’s to connect directly with the past.

I’ve collected oral histories for other projects and have observed how recollections become something like set pieces, almost to the point of using repetitive phrasing. Add the fact that memories deteriorate over time, and one has to view oral histories with a degree of caution. So this is the mindset I brought to my consideration regarding Stonewall.

Then I factored in three points that are rather unique to this history. First, a larger than normal percentage of the eyewitnesses are no longer with us. Some died in attacks of homophobic violence. Others died from AIDS or other illnesses. Still others just melted into society and have become lost to us. Second, the Stonewall riots have attracted more than the usual number of what I call aspirational participants, that is, people who represent themselves as participants in an event that they may, actually, not have attended. Sorting out the veterans from the wanabees can be challenging, as has been observed by Stonewall historian David Carter. Finally, the historical record is already rich with validated eyewitness accounts collected decades ago by Carter and others, recorded by documentary filmmakers, and archived in historical collections. I deferred to this vetted record, set down when the gap was narrower between event and retelling. I could not have hoped to improve on the way these recollections, clearly sourced in Stonewall, help to bring the history alive.

E.M.K.: You noted that it was somewhat difficult to document the role of lesbians in the events surrounding the riots. Why do you think that is?

A.B.: Because the Stonewall riots have come to represent this watershed moment in gay rights history, it is natural for all members of the LGBTQ+ community to look for their own “ancestors” in the events. The lack of information about lesbian participation in the riots can be frustrating until we remind ourselves that the Stonewall Inn was, after all, predominantly a hangout for gay men. It’s only natural that a raid of the place would have produced predominantly male participants in the melee that followed.

It doesn’t help that virtually all of the authors and filmmakers who’ve studied Stonewall have been men. I wonder to what extent the historical record has been skewed as a result. I found myself pouncing on every lesbian connection I could find, and I’ve woven those details into my book. I give full attention, as do others, to the person, probably a lesbian, who helped to inspire the growing crowd to begin demonstrating. Citing her own rough treatment by the police as a reason for action, she cried out a challenge, as she was being manhandled into a patrol car: “Why don’t you guys do something?!”

And they did!

E.M.K.: I was especially interested in the discussion of the laws that were manipulated by law enforcement and others in an effort to control and harass LGBTQ+ people in the time leading up to the riots. At what point in the research for Stonewall did you get interested in the legal aspects of the conflict?

A.B.: It always amazes me how those with power try to bend laws toward their own points of view. I saw this with the World War I-era suffragists from With Courage and Cloth who were arrested for random reasons such as “causing a crowd to gather and thus obstructing traffic” after they, as peaceful pickets, were physically attacked by opponents. Or how the Freedom Riders were arrested “for their own protection” when they reached Birmingham, en route from Nashville to Montgomery.

With Stonewall I learned early on that I had to pay close attention to the legal situation. I began my research thinking, as do most people, that the raid of the Stonewall Inn that provoked the famous riots was just another routine gay bar raid. Pretty quickly I learned that this was not the case, but it took quite a while to sort out the full picture.

Gay bars had actually become legal during the lifetime of the Stonewall (which opened in 1967). Neither the service of alcohol to gays or same-sex dancing remained illegal in 1969. So, as far as gay patrons were concerned, the era of gay bar raids should have been over (which had to have compounded the anger during the riot-producing raid). Police raided the Stonewall because of its Mafia connections and the suspicion that its owners were blackmailing patrons who might lose their jobs if their sexual orientations became known. Bribery can be hard to prove, so the police tried to shut the bar down based on technicalities regarding its liquor license. The raids were a way to collect evidence that the bar was operating without the proper license.

You never know what you’re going to have to understand when you start a research project, and I hadn’t anticipated the extent to which I’d have to master the shifting legal statutes. But, in order for the history to make sense to me, that’s what I had to do. And if I’m confused, the reader will be, too, so, on this one, it was back to the books, so to speak, until I’d sorted everything out.

E.M.K.: I can imagine those familiar with the Stonewall Riots and their place in the movement for LGBTQ+ rights would have expected the book might end with the relative freedom of the 1970s as compared to the time before the riots. Can you discuss your decision to look beyond that time to what came later in the movement for LGBTQ+ rights?

A.B.: It would have been a lot easier to stop there! I’d always envisioned, though, the need to carry the history forward. I felt that young readers would be left with a gap of knowledge otherwise and even, perhaps, confusion. What the heck happened, they might have asked? Why are we still fighting for LGBTQ+ rights? Didn’t things just get better and stay better after the Stonewall awakening?

History is rarely so tidy, though (because neither is life, and life becomes history). Social justice movements, in particular, tend to have peaks and valleys of momentum and slump. Fighters can have to scale that terrain multiple times in order to secure access to equal rights. So I wanted to give young people the fuller perspective on this social justice movement. Plus it’s just essential to talk about the impact of AIDS on the movement and on individuals.

I set out to write not just a history of the Stonewall riots but a history of them within the context of the gay rights movement. The fact that we are once again experiencing leaps of progress for LGBTQ+ rights gives readers the same closing uplift one might have created if the book had ended in 1970. I find it much more satisfying to have gone through darkness and once again come out in the light.

E.M.K.: You wrote in your author’s note about your inspirations for Stonewall and why you decided to pursue the project now. I was moved to read that you feel you wrote Stonewall “in the company of ghosts.” Can you talk about some of those ghosts?

A.B.: By the time I begin writing one of my books, I’ve spent a year or more researching it. That work builds until I feel very connected to the past. Usually I’ve visited the places I’m writing about, have handled primary source documents from those eras, and have inhaled so much information that I almost feel as if I’m breathing in past tense.

Often I know early on to whom I plan to dedicate a book. That connection is infused into my work. The closest analogy I’ve come up with is the feeling one can have when baking a cake for a loved one. There’s just extra love baked into that cake. I get the same feeling when I work on a book that will be dedicated to someone special.

With Stonewall I knew from the get-go that I would be dedicating my book to a close friend from college, Mike Bess, and that I wanted to acknowledge two other individuals as forces in my work: Tyler Clementi, the student from Rutgers, and Michael Riesenberg, a college friend who died at age 34 from AIDS.

Did I write in the company of Tyler’s ghost? I can’t say. But his death motivated me daily. But Mike Riesenberg’s spirit? The friend who died from AIDS? Perhaps yes. There is an odd coincidence I write about in my acknowledgments where I unintentionally researched his birth on what turned out to be his actual birthday. That was a goose bump moment. But, beyond Mike, I felt the weight of all the brothers and sons and fathers who died too young because of AIDS. The more I researched AIDS, the more company I felt in my work.

On the side, while I was researching Stonewall, I read David Levithan’s Two Boys Kissing. I understood immediately his chorus of voices from beyond. They spoke to me, too. Not with words, but with energy that fueled my work, just as the rage and sadness I’d felt at Tyler’s death fueled my work. Did I see any ghosts? No. But did I feel them? You bet.

And I welcomed their company.

E.M.K.: Did anything in the research for Stonewall really surprise you?

A.B.: Well I wasn’t expecting those ghosts!

Beyond that, I think what surprised me the most was the level of personal shock and discovery that I encountered through my research. I learn a tremendous amount whenever I research a book, but in the case of Stonewall I really was starting with the most rudimentary base of knowledge, so I had to fill in a lot of gaps. Over and over and over I found myself gasping at discoveries, shaking my head, feeling ashamed for my country’s past. I truly had not expected to find this depth of oppression and despair and misery. Yet it made the history make sense.

Although such discoveries were disheartening, they were also empowering. Every find affirmed that this story had to be told and gave me more strength to bring it to life. We talk about gay pride. We talk about coming out. I wanted to do the history proud. I wanted to bring it out into the open. And that became my goal for Stonewall: Share the history, out and proud!

Thank you, Ann, both for Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights and for sharing your insights and the process behind this extraordinary book.

Ann Bausum writes about U.S. history from her home in Wisconsin, and speaks across the country about her work as an author. Her books for young people help upper elementary, middle school, and high school students discover the drama and significance of stories from history that may barely be presented in their textbooks. Her goal is to make history relevant, engaging, alive, and irresistible.

Ann Bausum writes about U.S. history from her home in Wisconsin, and speaks across the country about her work as an author. Her books for young people help upper elementary, middle school, and high school students discover the drama and significance of stories from history that may barely be presented in their textbooks. Her goal is to make history relevant, engaging, alive, and irresistible.