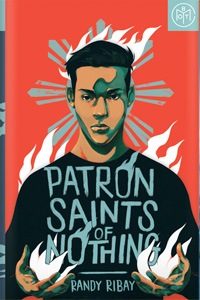

In a time of growing authoritarianism and disrespect for basic human rights, the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines stands as one more example of a people choosing terror and violence carried out by their own government. In his third YA novel, Patron Saints of Nothing, Filipino-born author Randy Ribay captures the complexity of life in a country where an elected – and still popular – leader rules through fear, as seen through the eyes of young people whose instinct is to rebel against the social structures and strictures of their elders.

In a time of growing authoritarianism and disrespect for basic human rights, the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines stands as one more example of a people choosing terror and violence carried out by their own government. In his third YA novel, Patron Saints of Nothing, Filipino-born author Randy Ribay captures the complexity of life in a country where an elected – and still popular – leader rules through fear, as seen through the eyes of young people whose instinct is to rebel against the social structures and strictures of their elders.

The son of a Filipino father and white North American mother, Jay Reguero has grown up in comfortable circumstances and taken his privilege for granted. Through he prefers video games to his studies, he’s disappointed that he has to attend a state university instead of the elite private colleges that rejected him due to his mediocre academic record. All this changes when he parents tell him that his cousin in the Philippines, Jun, was shot and killed as part of Duterte’s murderous campaign against drug dealers and users.

In a visit to the Philippines eight years earlier, Jay and Jun forged a close connection. They were only three months apart in age and both displayed a sensitivity that seemed impractical in a poor, highly unequal country with a history of brutal dictatorship. Over the years, they exchanged heartfelt letters, but Jay, busy with a girlfriend and fun, stopped writing. His sense of loss, guilt, and unfinished business takes him on a spring break trip to the country of his birth, where, in trying to clear his cousin’s name, he uncovers longstanding conflicts and secrets.

Ribay is a master of the road trip novel, and Patron Saints of Nothing takes readers to Manila’s prosperous suburbs – where Jun’s father, a high-ranking police inspector, lives – and to the city’s most desperate slums. All along, Ribay keeps readers guessing; like Jay, we come to see that things aren’t at all what they seem. At one point, Jay’s lesbian aunt provided a way station for Jun, and she does the same for Jay, as he discovers the challenges that LGBTQ+ people face in a devoutly Catholic country not known for its liberal social views. One of Jay’s other uncles is a priest, and a stop at his church leads Jay (as well as Jun before him) to ponder the historic role of the Church amid corruption and poverty and what God and the saints wanted for the world. Ribay’s novel is most powerful when it shows Jay uncovering the roots of his cousin’s despair, and the green shoots of hope in the lives of those who remain.

An author’s note following the novel provides resources about Duterte’s war on drugs (and dissent) and the thousands of lives it has claimed.